12 Japanese New Year’s Traditions and Greeting Messages

Table of Contents

Just like that first gust of cold winter wind that catches us off guard, the arrival of a new year can sneak up on us before we even get a chance to make our New Year’s plans (let alone our resolutions). Fortunately, Tippsy has got you covered, for as long as you’ve got a good bottle of sake on hand, you can bid the New Year welcome wherever your plans may take you. After all, premium sake brewed with utmost attention and care is a special drink that befits a holiday like New Year’s, when even the most bookish among us get caught up in the merriment and raise our glasses to toast in unison.

Sparkling sake on New Year’s Eve is as safe (and delicious) a bet you can make. Opening a bottle of Hakkaisan “Awa” Clear Sparkling is a great way to bring out the bubbles. This sake was developed specifically to be used to commemorate the 2020 Olympics and owing to its popularity, the Niigata global juggernaut Hakkaisan has brought it back every year since.

You can also go the Lunar New Year route and find sake that fits with the zodiac theme. For example, 2024 is the year of the dragon, so a bottle like Ryujin “Kakushi Ginjo” would be perfect. Ryujin refers to the dragon god of the sea, and “kakushi” means secret. But don’t keep the secret of delectable sake to yourself — share it with your companions and raise your glass high!

If there was a sake brewed to toast the times, this could be it: a super premium sake like Shichida “Junmai Daiginjo.” It comes from a stellar brewery in Saga prefecture where even the water itself is good enough to bottle. A wonderful aperitif but also food-friendly, this sake will serve you well from hors d’oeuvres straight through to the New Year’s countdown — if you have the willpower to let it last that long.

Still not sure which sake is the best for your celebration? Tippsy has many more recommendations, especially for newcomers to the sake world. But sake is just one aspect to consider. In Japan, there’s much more to Japanese New Year’s traditions than what’s in your glass. Let’s also take a look at some of the myriad Japanese customs that revolve around the arrival of the new year.

12 Japanese year-end traditions

Kagami mochi is one of the most common New Year’s decorations in Japan.

For most of us, beyond making a resolution, watching the ball drop, getting together with loved ones, and toasting with a glass of bubbly, there isn’t much more to commemorating the New Year’s holiday. There’s plenty of suspense and excitement leading up (or counting down) to New Year’s, but once it arrives, we try our best to stick to our resolutions and get on with life without much fanfare. Not so in Japan, where it is one of the most important times of the year for many Japanese; a span of days filled with rituals and practices that begin well before New Year’s Day itself. Here is an overview of some of the most common New Year’s traditions in Japan.

Ōsōji (deep cleaning)

While spring cleaning is a familiar concept to most of us in America, the annual tradition of cleaning away the dust and grime of the past year takes place around the new year in Japan. Since as far back as the Heian period (794-1185), the practice of cleansing the soot that collected from hearths and candles has been adopted as a tradition in Japanese homes.

“Ōsōji,” literally “big cleaning,” was adopted by ordinary folks during the Edo period (1603-1868), when shopkeepers, monks and commoners alike all stopped what they were doing on Dec. 13 to conduct ōsōji. Castles, shops and private homes were all cleaned in preparation for the New Year, and it marks the first day of New Year’s celebrations. Even though the hearths and candles have since been largely replaced by electricity, this custom carries on as a way to leave a spotless space for New Year’s decorations. I think there’s some wisdom in getting such a task done during the colder months, when there’s not a whole lot to do outdoors!

Enjoy joya no kane (midnight bells)

A solemn alternative to the often raucous New Year’s Eve celebrations that many of us are familiar with, “joya no kane” is the traditional bell ringing that marks the closing of one year and the beginning of the next. Far from an arbitrary tolling to mark the time, the bells of many Buddhist temples in Japan are struck exactly 108 times, and are often timed to conclude as the last moment of the year comes to a close. There are various explanations as to the reason for this exact number, but prominent among them is the Buddhist belief that the total number of worldly desires works out to 108. By striking the bell 108 times, these temptations are thus cleansed.

In some cases visitors are allowed to take part in the striking of the bell, and in some cases this task is left to temple officials. With the final toll of the bell marking midnight, spectators are left contemplating the start of a new year amid the reverberations of the last. If you are in Japan and plan on visiting a joya no kane ceremony, make sure that you arrive early to witness the full spectacle of the bell ringing and enjoy the “amazake” (a porridge-like fermented rice drink) and food that some temples have on offer.

In the U.S., the Betsuin Buddhist Temple in Seattle holds a joya no kane ceremony that is open to the public from noon to 1 p.m. on New Year’s Eve. In Los Angeles, the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple also holds a joya no kane ceremony. Check the temple pages for details, or search for one near you.

Eat toshikoshi soba (New Year’s soba)

Soba noodles can be eaten cold or warm, but for New Year’s soba, warm is customary.

“Ōmisoka” or New Year’s Eve in Japan would not be complete without food, so let’s dig in! The first and most symbolic dish — and one that will warm you up after a night out listening to the bells ring or watching the ball drop — is toshikoshi soba, or “year-crossing soba noodles.” Like many traditions in Japan, toshikoshi soba began centuries ago, and was limited to the elite, but caught on among average citizens later during the Edo period. Consuming toshikoshi soba is said to bring good fortune in the coming year. Explanations abound for the symbolism of this dish, from the long noodles/long life comparison to the toughness of the buckwheat crop. This dish is also said to represent breaking free from the past.

This symbolic dish, consisting of soba noodles in dashi and garnished only with finely chopped scallion, is quite simple, delicious and accessible to most of us, so why not give it a try? You don’t have to be superstitious to enjoy it, but you could double down on your good fortune by pairing some toshikoshi soba with the versatile and food-friendly Wakaebisu “Honjozo,” whose label is emblazoned with the god of good fortune himself. This light and dry sake falls right in line with the straightforward nature of this dish.

Watch hatsuhinode

On the surface, the logic behind the tradition of “hatsuhinode” is simple: If seeing the sun rise in the morning can change your outlook on a day, then bearing witness to the first sunrise of the new year is bound to help you “reset” for the year. But the origin of this tradition actually has deeper roots: It was thought that Toshigami, a spirit associated with good luck and the passing of time, used to appear at sunrise on the first day of the new year. While you may be able to appreciate the sunrise wherever you live, finding a special scenic spot nearby will surely heighten the sense of drama, positivity, and maybe even your good fortune. At the very least, it will certainly make your moment more Instagrammable.

Try Japanese New Year decorations: Shimekazari, kadomatsu and kagami mochi

Owing to the fact that January is the time of year when Toshigami-sama is believed to visit Japanese homes to bring good fortune and happiness, the tradition of New Year’s decorations in Japan is quite distinct, purposeful and rich with symbolism.

“Kadomatsu” are decorations set up at the entryway to let the deity know this particular place is welcoming. Boughs of pine, being evergreen, are specifically used to represent strength and resilience. Bamboo, also green throughout the year, arrow-straight, sturdy and fast growing, is also used. Plum sprigs, a symbol of righteousness, are added as an accent, showing that flowers can bloom even during colder times. The pines, bamboo and sprigs are bound in a cylindrical basket and are playful and festive without being gaudy.

Shimenawa is a beautiful, traditional New Year’s decoration with roots in the Shinto religion.

“Shimenawa,” a woven straw festoon, serves a similar purpose as kadomatsu, indicating a sacred space. The components of the decoration are carefully chosen for their symbolic meaning as well: Fern, for honesty and longevity; and orange, for family prosperity. Yuzuriha, a shrub whose leaves do not fall away until a new replacement grows beneath it, represents amity between succeeding generations.

Kagami mochi is a pair of mochi rice cakes stacked smaller on larger, the round shapes of which represent one of the three sacred treasures of Japan: a copper mirror whose origins date all the way back to the Yayoi period (300 B.C.-300 A.D.). The mirror, able to reflect the sun, was used as a device to summon the sun goddess, Amaterasu Omikami. An added layer of meaning of kagami mochi is that the use of rice from the past year’s harvest creates a display of gratitude. Kagami mochi is typically displayed in the “kamidana” (household altar) or “tokonoma” (elevated alcove), but you can display your kagami mochi in any place of importance in your home.

Eat traditional New Year’s food

For home cooks with an Asian specialty market nearby, enjoying traditional Japanese New Year’s food may be the most accessible way to get into the New Year’s spirit. If you’re not looking to add to your holiday cooking and cleaning workload, major metropolitan Japanese restaurants near you may have something planned for the occasion.

The weeks before and after New Year’s Day often find families and neighbors coming together to enjoy fresh, hand-hammered mochi in a tradition called “mochitsuki.” Mochi rice that has been soaked overnight is steamed and placed in a large mortar, then pounded (with varying degrees of theatricality) with a large wooden mallet called a “kine.” After the mochi is pinched off into bite sized pieces, it is rolled in rice flour or other toppings and shared while it’s still warm and chewy — so soft and chewy that local authorities remind revelers each year not to let the elderly eat mochi, as it can be a choking hazard. This tradition, which started during the Heian period, has grown in some places to an all-out festival complete with New Year’s activities, amusements and performances. There may even be a celebration near you! And if not, mochiko (mochi flour) is relatively easy to come by these days and is even possible to make in the microwave — no giant pestle and hammer required.

Boxes of osechi are a feast for the eyes as much as the stomach!

For fans of bento cuisine, the arrival of New Year’s centers around the tradition of osechi ryōri, which contains a sampling of carefully chosen traditional Japanese recipes all artfully arranged in special stacking boxes called “jubako.” Each dish is symbolic in its own way, and the meal as a whole is a ritual that conveys good fortune for the year to come. Datemaki, a kind of rolled omelet, brings a mix of sweet and savory to the meal and is easily recognizable with its festive flower-like shape. Ebi no umami, or simmered shrimp, brings color and flavor from a careful overnight preparation. Different regions and families have their own variations and favorites, but dishes are carefully combined to balance flavor, color, seasonality and symbolism. With the ever-growing number of authentic Japanese restaurants and eateries around the U.S., landing some jubako for your New Year’s celebration has never been easier. But beware, most restaurants take orders for osechi days if not weeks in advance.

Osechi ryōri

New York City: Sunrise Mart, Wasan Brooklyn

D.C.: Sushi Gakyu

Seattle area - Uwajimaya

Mitsuwa locations (national)

Mochitsuki/New Year’s festivals

Seattle (Bainbridge Island) Mochitsuki

Hand out otoshidama

While many of us are familiar with gift giving around either Hanukkah or Christmas, the start of the new year in Japan is also a time for spreading happiness through generosity. “Otoshidama” are gifts of money given by adults to children and placed in festive and stylized envelopes. No particular amount of money is prescribed, but typically the closer the relationship of the adult to the child, the more generous the gift.

It is believed that the gift originated during the Edo period when wealthy families would send servants home with pieces of kagami mochi (wherein the god of good fortune, Toshidama, resides). This was thought to spread good luck. Over time, this tradition evolved to its current form, and the name Toshidama is used to refer to the cash-filled envelopes. Children are encouraged by parents to save a portion of the money for their future and to foster the good habit of saving. The decorative theme of the envelope can be virtually anything, but often the zodiac year is chosen.

Buy fukubukuro (lucky bag)

With all the wishes and blessings of good fortune to start off the year, you might just be tempted to test your luck. Thankfully, “fukubukuro” are popular this time of year. These lucky bags are grab bags of sorts, wherein shops randomly assemble discounted items. Customers love fukubukuro because there is an element of surprise to the transaction as well as the chance of a good deal. Merchants love them because they are able to clear their shelves of last year’s merchandise.

Go to hatsumode

A large crowd of people gathers for hatsumode at Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

In addition to the above-mentioned joya no kane, it is also common to save room for a temple visit in your busy New Year’s Day schedule. The tradition of “hatsumode” is just that: visiting a temple or shrine to pay your respects and pray for good fortune for the coming year. Hatsumode literally means “first visit,” and an estimated 100 million Japanese perform hatsumode on the first days of the year. Gohyakurakanji Temple is a popular spot in Tokyo that requires reservations for hatsumode, but provides toshikoshi soba, as well as an opportunity to ring the temple bell in their joya no kane celebrations.

Seattle area: Tsubaki Grand Shrine

Portland, Oregon: Konko Church of Portland

Los Angeles: Koyasan Beikoku Betsuin

Get omamori and omikuji

“Omamori” are talismans carried as a sort of lucky charm. What began centuries ago as a simple amulet to ward off evil has evolved into charms for a variety of purposes, such as success in education, success in love, financial fortune, or safety while traveling. But it is not as simple as just buying an omamori from the internet. Omamori, in their silken pouches, only have power if they come from a temple and have been blessed by a Shinto priest. Their power supposedly wears off after a year, which is why New Year’s is a popular time to power up your fortune with some fresh omamori.

If you do find yourself in possession of a genuine omamori, make sure that you always carry it with you and that you never open it for any reason. Omamori cannot protect you unless they are on your person, and opening them up allows the blessing to escape.

“Omikuji,” on the other hand, are random predictions of fortune for the coming year that hopeful souls can purchase at temples in Japan. The pre-printed fortunes are issued on simple white paper and give a general outlook for your coming year, and like the familiar horoscope section, mix in some specific predictions with regards to certain areas of life such as business, health, and of course, love. Sold at temples for around 200 yen, omikuji are a fun way to support your local temple. But fear not: even if you receive an omikuji predicting “kyo,” or bad luck, there are ways of dealing with that. Simply tie your bad fortune to the nearest tree or hanging wall inside the shrine grounds and carry on.

Send nengajo

Sending “nengajo” is a tradition that many of us are quite familiar with, as many of us send holiday postcards already, and nengajo aren’t that much different. Sending New Year’s greetings has been practiced by nobles since the Heian period, and became widespread with the development of the Japan postal service in 1871, when the printing of postcards began. Far from elaborate, nengajo usually have the year’s zodiac sign and bear a simple, sometimes pre-printed message that serves the purpose of extending greetings and well wishes for the coming year to the people in your life you are unable to greet in person. Since they are meant to coincide with the New Year, it is best to get an early start on writing your nengajo and drop them off at the post office in early December.

Nengajo can be hard to find stateside, but Amazon.jp has some for sale.

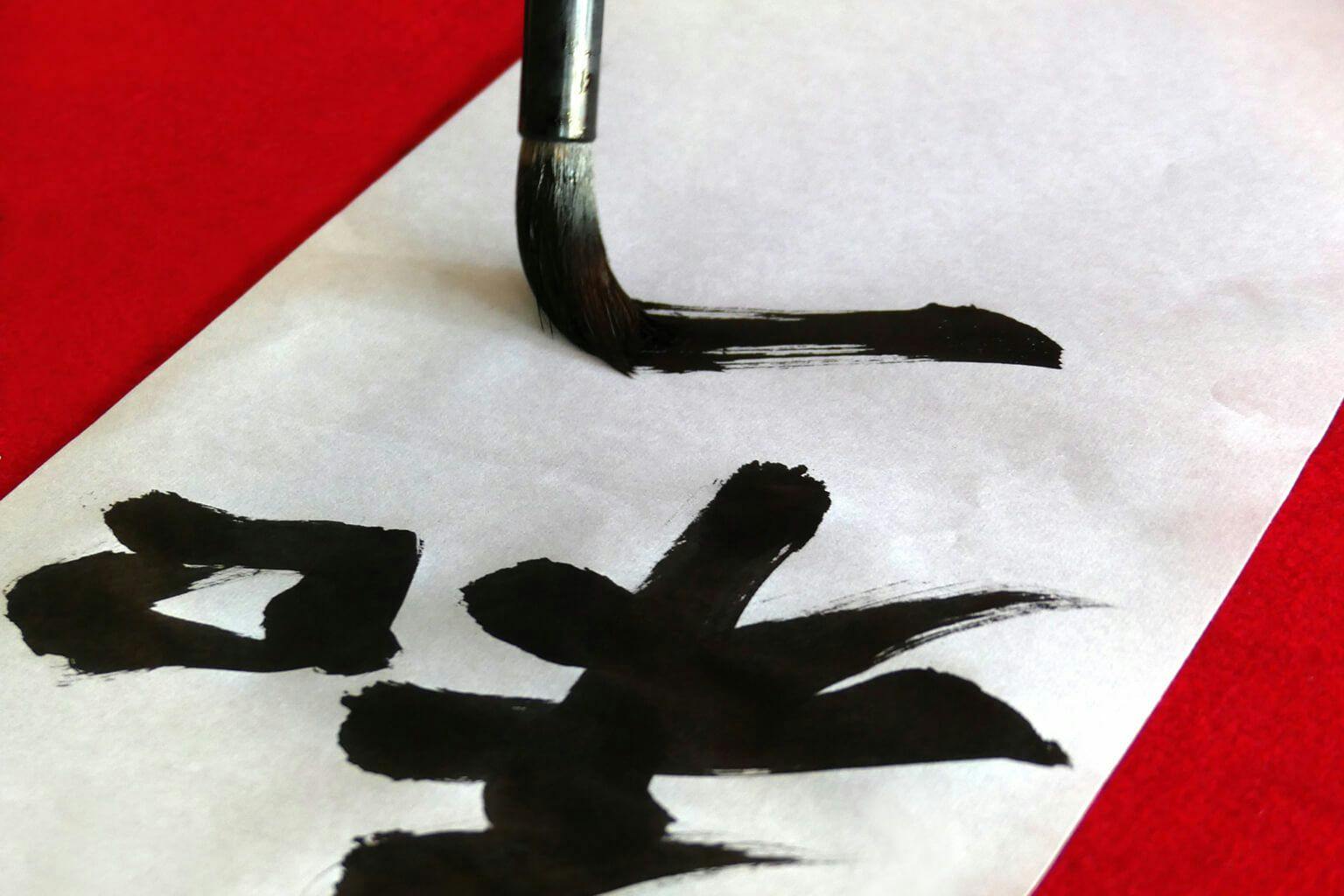

Try kakizome

Calligraphy is an ancient practice that still continues to this day.

For those that believe in the power of visualization, “kakizome” has your name written all over it. Pun intended, for kakizome translates to “first writing of the year.” Like many other Japanese New Year traditions, kakizome began with nobility and became popularized during the 19th century, with the belief that in some sense, you are what you write. Calligraphy is taught in schools in Japan, and there exists a sense of pride in handwriting. If there is something you wish to achieve, there is the belief that putting it into writing moves you one step closer to realizing what you’re after. “Shodō” (Japanese calligraphy) aficionados know well that the practice of writing with ink and brush carries with it a sense of relaxation and mindfulness, where every stroke and dash are traced with intent. For all these reasons, picking up brush and paper is as good a way to start the year as any.

Popular kanji for kakizome include 希望 (hope), 平和 (peace), 旅 (journey), 夢 (dream), and 喜 (happiness).

Japanese New Year greeting examples

With so many Japanese traditions to choose from, all that’s left (aside from sake) is spreading the New Year’s cheer. Here are some New Year’s greetings and when to use them:

“Yoi otoshi wo omukaekudasai” 良いお年をお迎えください: Have a wonderful New Year’s (future tense, before Jan.1)

“Akemashite omedetō gozaimasu” 明けましておめでとうございます: Happy New Year (present tense, on or after Jan.1)

Among co-workers and in formal settings, you might express your wish for a colleague’s continued goodwill and thanks for the New Year by saying: “Akemashite omedetō gozaimasu. Kotoshimo yoroshiku onegai shimasu” (今年もよろしくお願いします) This can be shortened when with close friends to: “Ake ome! Koto yoro!” (あけおめ!ことよろ!)

Celebrate New Year’s with quality sake

With all of these traditions, courtesies and greetings that go along with New Year’s in Japan, the reverence for this time of year is overflowing — but what about your cup? Is there sake in it? If your New Year’s resolution is to drink more good sake, there has never been a better time to do so. Tippsy’s guide for the best bottles for beginners takes the uncertainty out of swapping your Champagne for sake, and for those veteran sake drinkers out there, the arrival of a new year is as good an excuse as I can think of to grab a special bottle (or three!) and treat yourself. Happy New Year’s, and kampai!

Resources

Hirasawa Chen, N. “Osechi Ryori (Japanese New Year’s Food) おせち料理.” Just One Cookbook. Nov. 18, 2023.

https://www.justonecookbook.com/osechi-ryori-japanese-new-year-food/

Hirasawa Chen, N. “Toshikoshi Soba (New Year’s Eve Soba Noodle Soup) 年越しそば.” Just One Cookbook. Aug. 2, 2023.

https://www.justonecookbook.com/toshikoshi-soba/

Weber, C. “Omamori: Japan’s Lucky Charm.” Japan House Illinois College of Fine & Applied Arts.

https://japanhouse.illinois.edu/education/insights/omamori

Yamauchi, Y. “First sunrise of the year brings luck.” The Japan Times. Dec. 29, 2016.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2016/12/29/lifestyle/first-sunrise-year-brings-luck/

Yamaguchi, D. “Hatsumode – A First Visit to Tsubaki Shrine.” The North American Post. Jan. 13, 2023.

https://napost.com/2023/hatsumode_0113/

Yamano, Y. “Japanese New Year’s Decorations.” Seattle Japanese Garden. Dec. 9, 2021.

https://www.seattlejapanesegarden.org/blog/2021/12/7/japanese-new-years-decorations

Yamano, Y. “Oosoji (大掃除), Japanese Big Year-End-Cleaning.” Seattle Japanese Garden. Dec. 9, 2022.

https://www.seattlejapanesegarden.org/blog/2022/12/13/japanese-big-year-end-cleaning

“2023-2024 New Year’s Eve bell-ringing at Tokyo temple.” Time Out Tokyo. Dec. 15, 2023.

https://www.timeout.com/tokyo/things-to-do/tokyos-top-ten-new-years-eve-bells

“Authorities urge elderly people to be careful when eating mochi.” Japan Today. Dec. 31, 2021.

https://japantoday.com/category/national/authorities-urge-elderly-people-to-be-careful-when-eating-'mochi

“Draw an “Omikuji” Fortune Slip at Japan’s Temples or Shrines.” Japan National Tourism Organization.

https://www.japan.travel/en/japan-magazine/2007_omikuji/

“Japanese New Year Traditions: Fukubukuro Lucky Bags!” Japan National Tourism Organization. Jan. 12, 2023.

https://www.japan.travel/en/uk/inspiration/fukubukuro/

“Japanese Year-End Customs: Otoshidama - New Year’s Money for Kids.” Live Japan. Dec. 31, 2018.

https://livejapan.com/en/article-a0000768/

“Hatsumode in Tokyo: 2024 New Year temple and shrine visits.” Time Out Tokyo. Dec. 18, 2023.

https://www.timeout.com/tokyo/things-to-do/hatsumode-in-tokyo-traditional-new-year-visits-to-shrines-and-temples

“How To Say Happy New Year in Japanese.” Kanpai. July 13, 2023.

https://www.kanpai-japan.com/learn-japanese/happy-new-year

“Kakizome: The First Writing Of A Year.” Wonderland Japan. June 5, 2020.

https://wattention.com/kakizome-first-writing-new-year/

Kawano, K. “All You Need To Know About Japan’s ‘Nengajo’ New Year’s Cards.” Savvy Tokyo. Dec. 5, 2019.

https://savvytokyo.com/need-know-japans-nengajo-new-years-cards/

“Mochitsuki: A Japanese New Year’s Tradition.” Asahi Imports. Jan. 4, 2014.

https://asahiimports.com/2014/01/04/mochitsuki-a-japanese-new-years-tradition/

“Why Do Japanese Bells Ring 108 Times on New Year’s Eve?” The National Bell Festival, Inc. and Bells.org.

https://www.bells.org/blog/why-do-japanese-bells-ring-108-times-new-year%E2%80%99s-eve

Domenic Alonge

Domenic Alonge is an Advanced Sake Professional, International Kikizake-shi. His work in sake breweries in Japan, Europe and the U.S., as well as his experience as the owner of North Carolina’s first sake-only bottle shop inform his writing and his videos which he now creates as the Sake Geek. Follow him on YouTube and on sake-geek.com.

Learn about Tippsy’s Editorial process

Recent posts

All about sake

Sign up to receive special offers and sake inspiration!